In the aftermath of the COVID–19 pandemic when many organisations, families and individuals have had to adapt to the “New Normal”; it has become imperative that one has to improve one’s learning skills. The environment has rapidly changed with our homes doubling up as offices for the adults, schools for children, recreational area for the entire family as well as a refuge where one retreats to recharge one’s batteries.

Furthermore, the ways of work have changed with traditional in-person interaction being replaced with on-line meetings, schooling, dating; to mention but a few. All of these changes require individuals and organisations to understand the change and quickly learn how to respond effectively to the big shifts in the way society and institutions are operating. In the words of Brian Herbert, “The capacity to learn is a gift; the ability to learn is a skill; the willingness to learn is a choice”.

To enable you as learner to develop strategies to effectively enhance your learning skills. We shall draw from the research done by educational scholars1 who have devised various typologies of VARK (visual, auditory, reading / writing and kinaesthetic) styles of learning. Furthermore, we shall also pick insights from research in psychology and management; more specifically Erika Andersen’s article on Learning to Learn2 where she identified some fairly simple mental tools anyone can develop to enhance all four attributes (aspiration, self-awareness, curiosity and vulnerability).

VARK Learning Styles

The acronym “VARK” is used to describe four modalities of student learning that were described in a 1992 study by Neil D. Fleming and Coleen E. Mills. These different learning styles—visual, auditory, reading/writing and kinaesthetic—were identified after thousands of hours of classroom observation.

Visual Learners: best take in and make sense of information when it is presented to them in a graphic depiction of meaningful symbols. Such individuals tend to be holistic learners who process information best when it is presented to them as a whole rather than bit by bit. They prefer to see the big picture first. As an Executive Coach, I have learned the importance of quickly assessing my clients and using appropriate visual aids to enable visuals learners to appreciate the entire coaching journey and specific issues at hand.

Auditory Learners: are most successful when they are given the opportunity to hear information presented to them vocally. Such individuals may sometimes prefer not to take notes during a training session in order to concentrate on listening to the trainer. Auditory learning is usually a two-way street, and during training sessions we have found that such individuals often enhance learning through group activities where they are asked to vocally discuss issues with their contemporaries; and they also benefit from reading their written work aloud to help them think it through.

Reading/Writing Learners: work best in the modality that includes both written information presented in form of handouts, online research and PowerPoint slide presentations, as well as the opportunity to synthesize data into written assignments.

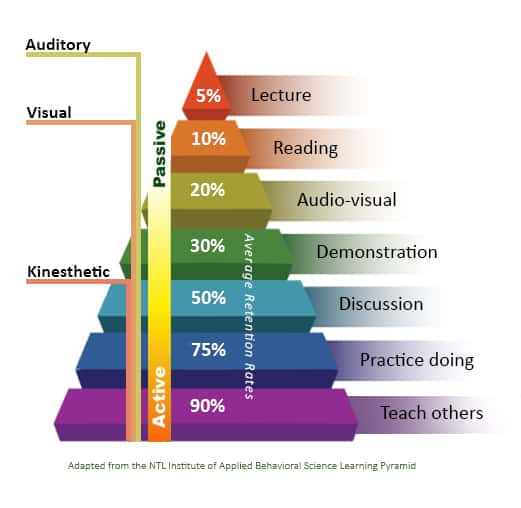

Kinaesthetic Learners: are hands-on, participatory learners who need to take a physically active role in the learning process in order to achieve their best educational outcomes. As a seasoned facilitator for several leadership programs at Imprint, I have found that utilizing interactive experiential physical activities tends to engage participants mentally as well as all of their senses equally in the process of learning. Furthermore, research indicates that the more active learning associated with kinaesthetic learners tends to have higher average retention levels than the passive learning associated with lectures and reading learning style.

Given that individuals may have affinities to different styles of learning; settings that engage them with multiple learning styles alternately or in concert with one another are likely to improve their learning skills.

Whilst “…the ability to learn is a skill; the willingness to learn is a choice”; and the willingness to resist the bias against doing new things, scanning the horizon for growth opportunities, and pushing yourself to acquire radically different capabilities while still performing your job; is definitely a choice that one must make. Erika Andersen argues that this choice requires a willingness to experiment and become a novice again and again: an extremely discomforting notion for most of us. She identified four attributes that are common learning tools: aspiration, self-awareness, curiosity, and vulnerability.

Aspiration can be defined as hope, desire or ambition to achieve something. Great learners can raise their aspiration level—and that’s key, because everyone is guilty of sometimes resisting development that is critical to success. Andersen argues that it’s easy to see aspiration as either there or not: You want to learn a new skill or you don’t; you have ambition and motivation or you lack them. When confronted with new learning, this is often our first roadblock: we focus on the negative and unconsciously reinforce our lack of aspiration.

During the COVID–19 aftermath that entailed social distance and a virtual lockdown in Uganda, my mother–in-law Hon. Joyce Mpanga, at the grand age of 88 years, embarked on learning how to use various social media platforms that included WhatsApp, YouTube, Twitter and Zoom to enable her to maintain her social obligations, be it virtually. Her desire to remain socially connected inspired her to start learning a range of technological skills that have enabled her to remain connected to her social circle despite the physical constraints of the current COVID–19 lockdown.

Self-Awareness: our assessments of ourselves—what we know and don’t know, skills we have and don’t have—can still be woefully inaccurate. It is argued that the people who evaluate themselves most accurately start the process inside their own heads: They accept that their perspective is often biased or flawed and then strive for greater objectivity, which leaves them much more open to hearing and acting on others’ opinions. The trick is to pay attention to how you talk to yourself about yourself and then question the validity of that “self-talk.”

Let’s say your boss has told you that your team isn’t strong enough and that you need to get better at assessing and developing talent. Your initial reaction might be something like “What? She’s wrong. My team is strong.” Most of us respond defensively to that sort of criticism. But as soon as you recognize what you’re thinking, ask yourself, “Is that accurate? What facts do I have to support it?” In the process of reflection, you may discover that you’re wrong and your boss is right, or that the truth lies somewhere in between—you cover for some of your reports by doing things yourself, and one of them is inconsistent in meeting deadlines; however, two others are stars. Your inner voice is most useful when it reports the facts of a situation in this balanced way. It should serve as a “fair witness” so that you’re open to seeing the areas in which you could improve and how to do so.

Curiosity: Kids are relentless in their urge to learn and master; and curiosity is what makes us try something until we can do it, or think about something until we understand it. Great learners retain this childhood drive, or regain it through another application of self-talk. Instead of focusing on and reinforcing initial disinterest in a new subject, they learn to ask themselves “curious questions” about it and follow those questions up with actions.

I was intrigued by my 8-year-old nephew who was attending an online classroom session with his young colleagues. The kids had learned how to navigate through the different attributes of Zoom such as raising their hands, knowing when to mute their microphones or switch on their videos. I observed that curiosity was key to their learning and similarly many leaders who have mastered the art running webinars, online conference calls have been driven by responding to their curiosity of exploring the unknown.

Vulnerability: Andersen argues that once we become good or even excellent at some things, we rarely want to go back to being not good at other things. Yes, we’re now taught to embrace experimentation and “fast failure” at work. But we’re also taught to play to our strengths. So, the idea of being bad at something for weeks or months; feeling awkward and slow; having to ask “dumb,” “I-don’t-know-what-you’re-talking-about” questions; and needing step-by-step guidance again and again is extremely scary. Great learners allow themselves to be vulnerable enough to accept that beginner state. In fact, they become reasonably comfortable in it—by managing their self-talk.

My daughter Suubi has fascinated me with her tenacity to cope with change due to the different education systems she has been exposed to. During a difficult time whilst at Gayaza High School, Suubi personally adopted her school’s motto “Never Give Up” to seek support and guidance from her fellow students, teachers and other stakeholders until she excelled in her studies. Suubi has used the same approach in her different endeavours that include playing the Guitar, Piano, and Netball.

In a world that is experiencing rapid change following the COVID–19 pandemic, all of us need to enhance our learning skills despite our different learning styles; namely visual, auditory, reading / writing and kinaesthetic. The ability to acquire new skills and knowledge quickly and continually is crucial to success and this is driven by the aspiration, self-awareness, curiosity, and vulnerability to be an effective learner.

Dr Jeff Sebuyira Mukasa

BCom, FCCA, MBL, DBL

- Business, Consulting

No comment yet, add your voice below!